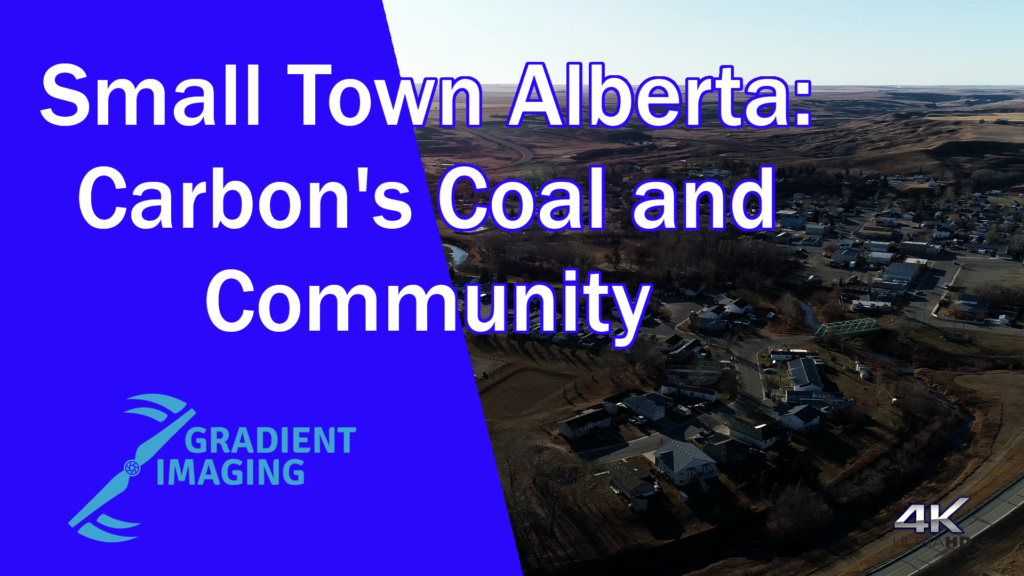

If you blink, you might miss Carbon, Alberta — a small village tucked quietly into the Kneehill Creek valley, about halfway between Drumheller and Three Hills. But if you slow down, if you roll through town with the window cracked and the radio low, you’ll notice that Carbon isn’t empty at all. It’s just taking its time.

The first thing that stands out is how green it feels for prairie country. The valley folds around the town like a shallow bowl, sheltering it from the wind that usually sweeps across central Alberta. The streets are lined with trees, a mix of older homes and newer builds that seem to coexist without fuss. There’s a curling rink, a school, a museum, and a campground that fills up on summer weekends. Nothing feels forced here — just steady, lived-in Alberta.

But for a town named Carbon, the real story runs a little deeper. The name wasn’t a poetic choice. It was practical — literal, even. When the post office opened in 1904, a rancher named L. D. Elliot suggested the name because of the coal buried beneath the valley. Within a decade, mining had turned this quiet settlement into a working town, its lifeblood tied to the black seams underfoot. By 1912, Carbon had officially incorporated as a village, right around the time the Canadian Pacific Railway came through to haul that coal away.

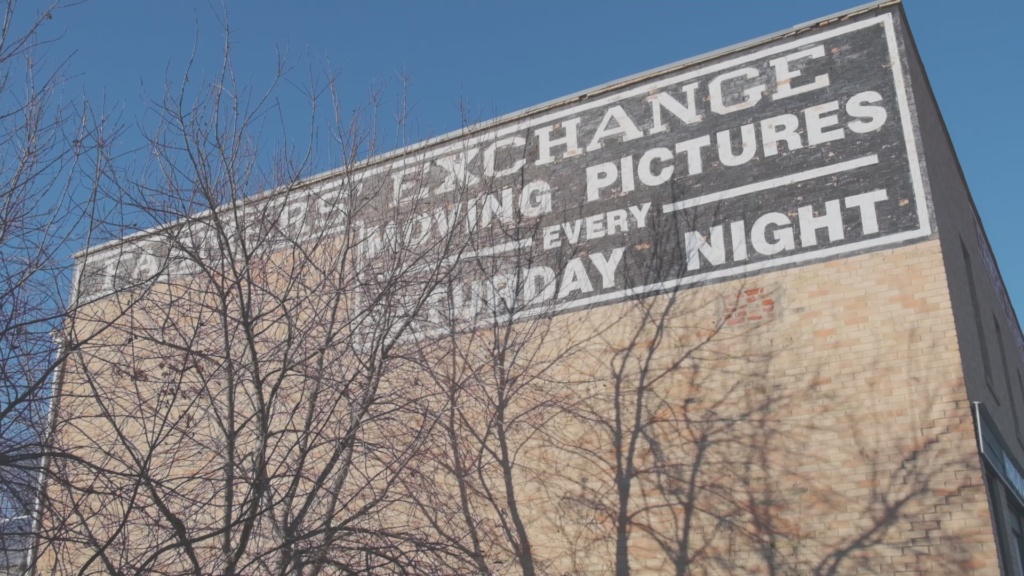

You can still trace the path of the old railway if you know where to look. The tracks are long gone, but the raised bed still cuts a clean line through the fields. For years, trains rumbled through town, loaded with coal and later with grain. The mines closed one by one through the mid-1900s, and the last elevator came down not long ago. But somehow, even without the clatter of industry, Carbon never really faded — it just adapted.

There’s a local museum in a converted church that tells much of this story. Inside, you’ll find photographs of soot-covered miners standing shoulder to shoulder, smiling for the camera after a long shift. Out back, there’s an old rail cart and a scattering of mining tools, reminders of when this quiet valley was buzzing with work. A little further up the road, the Kneehill Creek still winds through the trees, shallow and slow, feeding into the Red Deer River. In the summer, kids splash in it, same as they did a hundred years ago.

One of Carbon’s quirks is how it feels hidden in plain sight. Travelers on Highway 9 or 21 could drive right past without realizing a village sits just a few minutes off the route. Locals don’t seem to mind that. There’s a peaceful pride in being a bit off the beaten path. It’s the kind of place where you can leave your car unlocked, where folks wave even if they don’t know you, and where the sound of the train whistle — though long gone — still feels like it’s part of the landscape.

When you stand on Main Street and look around, you can still feel the weight of its name. Carbon — a simple, sturdy word for a place built on the stuff that once fueled half the province. The mines are gone, the railway’s quiet, but the story didn’t end there. It just settled in, the way small towns do, carrying its history quietly in the walls of its buildings and the rhythm of its days.

Carbon isn’t a town you visit for spectacle. You visit to remember what Alberta once looked like, and what it still is in places the highways forgot to modernize. A village built on coal, still standing on community. And maybe that’s the best kind of energy it could have hoped for.